The setting is the conference of the International Society for Music Education (ISME) in Interlochen, Michigan, in the USA in the summer of 1966. The Klemetti Institute Chamber Choir, conducted by Harald Andersén, is just finishing a performance of The Tomb at Akr Çaar by Bengt Johansson. After the final line of baritone soloist Matti Lehtinen, “I do not go…,” the piece dies out with a solo tenor whisper, “Nikoptis, Nikoptis, Niko…” A long electrified silence falls before the audience bursts into tumultuous applause which Andersén, the leading figure in Finnish choral music between 1960 and 1980, later described as one of the crowning moments of his life.

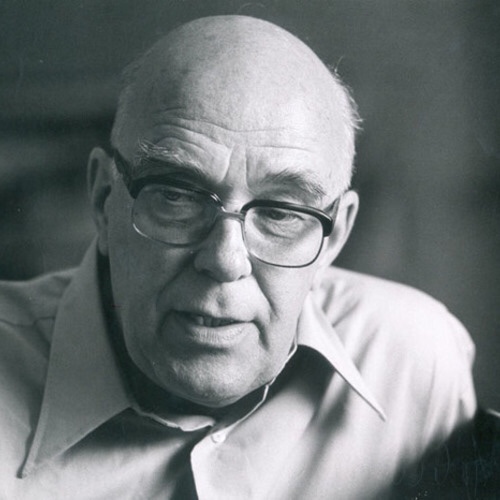

Bengt Johansson (‘ju:hansson’; 1914–1989) started out as a cellist and ended up as a sound technician and composer. As a composer, he was a student of both Leevi Madetoja and Selim Palmgren, and despite a great affection for early music and doubts about the limits of electronics in music, he wrote the first Finnish works for electronics (Three electronic etudes, 1960). That Johansson became a productive choral composer was in part due to his work as a sound technician for the Finnish Broadcasting Company. This position gave him a rare vantage point to the work Harald Andersén was doing with his new Radio Chamber Choir. Johansson saw and heard that here was finally a choir that could do justice to even the most demanding new choral works and was encouraged to try his hand. What followed in the 1960s and 1970s was a handfull of choral works of the highest quality.

The predominant textural solution in Johansson’s works for mixed choir is homophonic bitonality. Many of his works are scored for three female and three male voices with contrasting major/minor triads in both – most often the triad combinations are only mildly dissonant. The movement of these triads (at times parallel, at time in counter movement) creates shimmering, shifting sonorities. A prime example of this is Ione, dead the long year from Three Classical Madrigals (1967). For his choral works, Johansson mostly chose texts that were ancient in character: Latin texts from the antiquity, Biblical texts, and poems by Ezra Pound with their references to antiquity.

The tomb at Akr Çaar is a setting of an Ezra Pound poem (from the collection Ripostes, 1912) in which the soul of a dead, mummified body in an Egyptian grave reproaches the body. Somewhere lurking in Pound’s poem is the awareness that this monologue-dialogue that has been ongoing for five millennia is about to end as the Egyptian graves are opened one by one. Johansson manages to convey the boredom of the millennia, the closed-in space of the tomb, as well as the beauties of the outside world. The barytone soloist sings demanding free atonal melodies, the choir whispers and breaks out into bitonal harmonies – to begin with, the triads are added with sevenths to create complex harmonies and towards the end they are reduced to triads as peace slowly returns to the tomb.

It is very little short of scandalous that Johansson’s central works are not available on CDs or online. This is unfortunately true of The tomb at Air Çaar as well, so you will just have to trust me on this classic. The music fortunately is available and I recommend this work for anyone with an excellent choir and a soloist up for a real challenge. The audience will be just as blown away as it was in Interlochen in 1966. And you don’t only have my word on it. The composer himself said of the work: “Looking back, it feels like everything I’d done was preparation for that one work, which then opened up new paths for me”.

As I said, too little of Johansson’s music is easily accessible. I found a few pieces to give a better idea of Johansson’s style and choral writing.

- Pater noster (1968). This was the work that set the stage for the youth choir movement and its close ties to contemporary, modernistic music. The Tapiola Choir, Erkki Pohjola, conductor (recording from 1977)

- Kyrie from Missa a cappella (1969). This mass setting has had relatively few performances. It is easy to hear the composer’s love of Renaissance music. Coro del Conservatory de Música de Morón, Roberto Saccente, conductor.

- Examine me (1985). This is a late work, a setting of Psalm 139 from female voices. Its hooks are the pedal effects (10 soloists) in the outer sections and the beautiful, lilting central passage. Akademiska Damkören Lyran, Kari Turunen, conductor (2004)