I worked for a choral association in Finland in the early 1990s. One role I had was to edit the quarterly magazine, Sulasol. For the Autumn number of 1992, I commissioned an essay from Einojuhani Rautavaara and he delivered a fine piece on being an artist in a European cultural context. In the essay he spent some time describing his relationship with religion and the background of his sacred works. One element of religion he discussed was angels. Rautavaara wrote: “We are so used to thinking of angels in the classical kitsch swan-winged and pajama-clad form that the angels of my Angel series [a trio of orchestral works from the 1970s] have been misunderstood. The angels I had in mind belong to something like the [Rainer Maria Rilke] Duino Elegies, in which ‘ein jeder Engel ist schrecklich’. Masculine and terrifying.”

***

Rautavaara’s (1928–2016) father was an opera singer and he was immersed in music from an early age. Rautavaara lost both his parents by the age of sixteen and lived his last school years with a foster parent. One of Rautavaara’s favorite stories was a visit with a relative to Heikki Klemetti’s house in the late 1940s to see if Klemetti, the grand old man of choral music, thought the young man had enough talent to study composition. According to Rautavaara’s story, Klemetti said that Rautavaara’s works showed enough promise, but that it might be better to become a chauffeur, as they are paid better. Through the twists and turns of fate, Rautavaara not only became a composer, but even spent many of his later years in Klemetti’s house as a tenant.

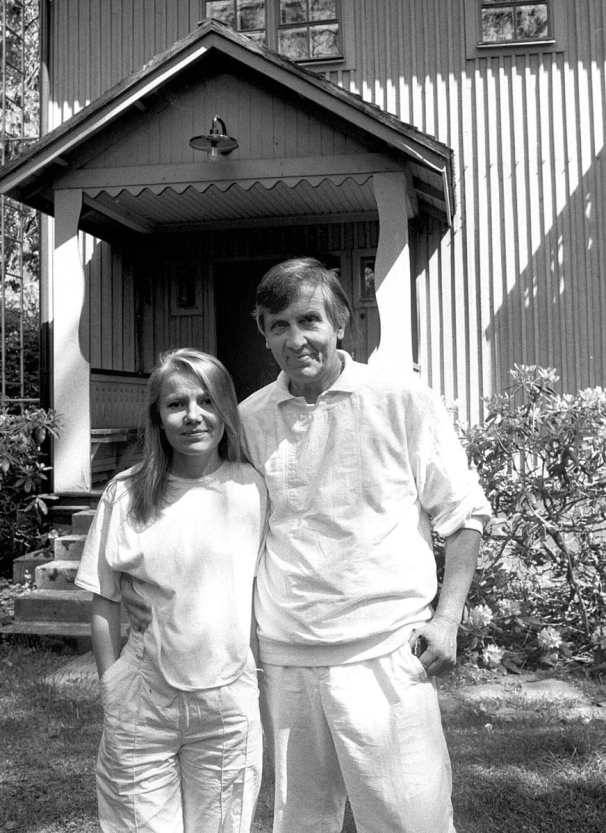

Rautavaara with wife Sini outside their home, Hopiala, previously Klemetti’s home

After studies at the University of Helsinki and the Sibelius Academy, where his composition teacher was Aarre Merikanto, Rautavaara had a more fruitful meeting with an even greater figure than Klemetti. The 90-year old Jean Sibelius had in 1955 chosen Rautavaara as the recipient of a scholarship to the Juilliard school and Tanglewood, and the two met in the prize-giving ceremony. Studies with Aaron Copland in New York, and later with Vladimir Vogel in Switzerland, helped make Rautavaara a cosmopolitan figure: fluent in many languages, well-read and independent in thought. With the exception of time served as a music critic and fifteen years as the professor of composition at the Sibelius Academy (1976–1990), Rautavaara made his living as a composer. He wrote big orchestral works, operas, chamber music – and a fantastic body of choral works. Any number of his works could have ended up on my list of Classics, and several of them can be heard on the playlist below.

***

I had a strong sensation that the angels Rautavaara mentioned in the essay were going to make a re-appearance in his future works, especially since the composer had revealed that he had been carrying a copy of the Rilke Elegies with him for decades. When I heard Rautavaara had written a new work for choir to the first poem of the Duino Elegies, I knew to expect something special. Die erste Elegie was premiered at the Europa Cantat festival in Herning, Denmark by the Eric Ericson Chamber Choir in July 1994, and it was indeed something special. Rautavaara later admitted that he had thought the commission was a little unreasonable as far as the length of the piece was concerned. He thought that a 10-minute, one-movement a cappella piece felt extremely long and it was a real challenge to write such a piece, let alone perform it. But he was satisfied with the premiere and the last 25 years have shown that while the demands of the work are considerable, they are by no means in surmountable.

In many ways, die erste Elegie is a summa of Rautavaara’s choral style(s). Melodic atonal rows, ostinatos in the bass line, triads being transformed into new triads by the movement of one note at a time, huge tessiraturas, wide leaps in the melodies and a sensation of forward movement are typical of Rautavaara’s choral works from the 1950s to 1990s. The textures are ‘orchestrated’ stylishly, even if the prevalent solution is four- to six-part harmony. It is uncanny how he manages to follow the text with great sensitivity and freedom within a strict technical framework.

The work consists of about a dozen sections and only twice does Rautavaara assist the performers with a sostenuto marking at the overlap. Based on Rautavaara’s guidance in the early recordings, it actually seems that he wanted the piece to flow freely from one section to another without too much separation. When you add to this flow the structure Rautavaara creates through the tempo relationships with a pulse that gradually grows faster, the ten-minute piece becomes one whole, with a feeling of inevitable heightening towards the broad ending.

Rilke’s poem contains multitudes of references and ideas. Even though Rautavaara sets only parts of the Rilke poem, he respects Rilke’s voyage from desperation (Who can hear me now; even the angels are terrifying) to hope (the void left by gods of old reverberates with music that comforts and lifts us). On the way there are so many fantastic lines that continue to haunt me, both the words and Rautavaara’s music. Like all great works of art, this is something one carries along on the journey through life and often returns to.

***

Rautavaara has such a wealth of brilliant choral works that I could easily have chosen any of almost ten works as the eight classic. His choral compositions are numerous and of extremely high quality. I would go as far to say that he belongs to the most important composers of choral music of the late 20th century.

- Ave Maria (1957). This early dodecaphonic work for male choir shows Rautavaara’s skill in combing modern techniques without breaking altogether with tradition. Amici Cantus, Hannu Norjanen, conductor.

- Avuksihuutopsalmi (Psalm of Invocation) from All-night Vigil (1971/72). An all-night vigil in the tradition of the Russian orthodox vigils was commissioned from Rautavaara, and, as was his wont, he conjured up music that continued a tradition, but renewed it at the same time. The Helsinki Chamber Choir / Niels Schweckendiek.

- Credo (1972). Rautavaara was a master at recycling his compositions. Credo is based on Partita for piano (1956), and appears again revised in Missa a cappella (2010-11). The Finnish Radio Chamber Choir / Timo Nuoranne.

- Le Bain from Elämän kirja (Book of Life, 1972). The Book of Life is Rautavaara’s most important work for male choir. The eleven movements to poems in different languages reveal the flexibility and sensitivity of Rautavaara’s music: when the language changes, the music changes. YL Male Voice Choir / Pasi Hyökki.

- El Grito (The Cry) from Suite de Lorca (1973). The early 1970s were a real sweet spot for Rautavaara and choral music. This suite, set to four poems by Frederico Garcia Lorca, was for decades the internationally best known and most sung contemporary Finnish work. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir / Paul Hillier.

- Sommarnatten (Summer Night, 1975). One of the most beautiful folk song arrangements ever written. Captures the Nordic summer night, nostalgia and the ecstasy of youth with astounding ease. Accentus / Eric Ericson.

- Quia respexit from Magnificat (1979). The Magnificat with five separate movements is one my great favorites in Rautavaara’s choral production. The textures are incredibly rich and sonorous, with diatonic fields formed with canons often framing beautiful melodic lines. The Finnish Radio Choir / Timo Nuoranne.

- Katedralen (1982). This work could just as well been our classic. It is a fantastic adventure of a piece, based on poems by the most important Finnish poet to write in the Swedish language, Edith Södergran (1892–1923). Not for faint-hearted performers. EMO Ensemble / Pasi Hyökki.

- Die erste Elegie (1993). Accentus / Eric Ericson.

- Freude steigt in uns auf & Meine Liebe from Wenn sich die Welt auftut (1996). An example of Rautavaara’s works for descant voices. This five-movement suite was composed for a German youth choir. The poems by Seppo Nummi were translated from Finnish into German, which gives them a hybrid color of their own. Akademiska Damkören Lyran / Kari Turunen.

- Ikävyys (Melancholy) from Halavan himmeän alla (1998). The three songs of Halavan himmeän alla were extracted from his opera Aleksis Kivi (1995–96). A new beauty crept into Rautavaara’s works in the latter 1990s. Kampin Laulu / Timo Lehtovaara.

- Agnus Dei from Missa a cappella (2010–11). Rautavaara’s last major contribution to choral music is an unaccompanied, 30-minute Mass. Its Agnus Dei is little more than a beautiful melody upon a chordal accompaniment. But when both melody and chords are well-nigh perfectly placed, the result is incredibly touching. The Latvian Radio Choir / Sigvards Klava.